News

Is a previously unheard-of First Nation just Canada’s latest Pretendian case?

Is a previously unheard-of First Nation just Canada’s latest Pretendian case?

Local chiefs claim Kawartha Lakes First Nation is part of a wave of cases in which people falsely claim Indigenous identity

he headquarters of the Kawartha Lakes First Nation sits off a single-lane highway 100 miles north-east of Toronto. Between signs advertising the sale of all-terrain vehicles, hand-scrawled messages on the three buildings decry government corruption.

At the centre of the lot, near signs for the “Redneck Church” and “Chief Willy’s Man Cave” stands a 26ft tipi. Alongside banners commemorating missing and murdered Indigenous women and the victims of Canada’s residential school system, Confederate flags flap gently in the wind.

To its 20 members, this is the heart of Canada’s newest First Nation. But seven local Indigenous chiefs claim it is the site of a brazen fraud that threatens to erode their hard-fought constitutional rights.

In recent years, Canada has grappled with a wave of “Pretendian” cases – in which people falsely claim Indigenous identity. Meanwhile, the use of Indigenous symbols and slogans has also grown increasingly common among the country’s far right.

Members of Kawartha Lakes First Nation argue they are exempt from laws and taxes, echoing the rhetoric of the extremist sovereign citizens movement, and the group’s emergence has raised concerns over how groups might use Indigenous identity to lay claim to land or demand concessions from local and provincial governments.

About two months ago, William Denby, the self-proclaimed “chief” of the Kawartha group began sending emails to local chiefs, municipal and provincial officials. The messages, seen by the Guardian, were often written in all caps and combined grievances and increasingly bold claims.

he headquarters of the Kawartha Lakes First Nation sits off a single-lane highway 100 miles north-east of Toronto. Between signs advertising the sale of all-terrain vehicles, hand-scrawled messages on the three buildings decry government corruption.

At the centre of the lot, near signs for the “Redneck Church” and “Chief Willy’s Man Cave” stands a 26ft tipi. Alongside banners commemorating missing and murdered Indigenous women and the victims of Canada’s residential school system, Confederate flags flap gently in the wind.

To its 20 members, this is the heart of Canada’s newest First Nation. But seven local Indigenous chiefs claim it is the site of a brazen fraud that threatens to erode their hard-fought constitutional rights.

In recent years, Canada has grappled with a wave of “Pretendian” cases – in which people falsely claim Indigenous identity. Meanwhile, the use of Indigenous symbols and slogans has also grown increasingly common among the country’s far right.

Members of Kawartha Lakes First Nation argue they are exempt from laws and taxes, echoing the rhetoric of the extremist sovereign citizens movement, and the group’s emergence has raised concerns over how groups might use Indigenous identity to lay claim to land or demand concessions from local and provincial governments.

About two months ago, William Denby, the self-proclaimed “chief” of the Kawartha group began sending emails to local chiefs, municipal and provincial officials. The messages, seen by the Guardian, were often written in all caps and combined grievances and increasingly bold claims.

Read More Is a previously unheard-of First Nation just Canada’s latest Pretendian case? | Canada | The Guardian

At the centre of the lot, near signs for the “Redneck Church” and “Chief Willy’s Man Cave” stands a 26ft tipi. Alongside banners commemorating missing and murdered Indigenous women and the victims of Canada’s residential school system, Confederate flags flap gently in the wind.

To its 20 members, this is the heart of Canada’s newest First Nation. But seven local Indigenous chiefs claim it is the site of a brazen fraud that threatens to erode their hard-fought constitutional rights.

In recent years, Canada has grappled with a wave of “Pretendian” cases – in which people falsely claim Indigenous identity. Meanwhile, the use of Indigenous symbols and slogans has also grown increasingly common among the country’s far right.

Members of Kawartha Lakes First Nation argue they are exempt from laws and taxes, echoing the rhetoric of the extremist sovereign citizens movement, and the group’s emergence has raised concerns over how groups might use Indigenous identity to lay claim to land or demand concessions from local and provincial governments.

About two months ago, William Denby, the self-proclaimed “chief” of the Kawartha group began sending emails to local chiefs, municipal and provincial officials. The messages, seen by the Guardian, were often written in all caps and combined grievances and increasingly bold claims.

he headquarters of the Kawartha Lakes First Nation sits off a single-lane highway 100 miles north-east of Toronto. Between signs advertising the sale of all-terrain vehicles, hand-scrawled messages on the three buildings decry government corruption.

At the centre of the lot, near signs for the “Redneck Church” and “Chief Willy’s Man Cave” stands a 26ft tipi. Alongside banners commemorating missing and murdered Indigenous women and the victims of Canada’s residential school system, Confederate flags flap gently in the wind.

To its 20 members, this is the heart of Canada’s newest First Nation. But seven local Indigenous chiefs claim it is the site of a brazen fraud that threatens to erode their hard-fought constitutional rights.

In recent years, Canada has grappled with a wave of “Pretendian” cases – in which people falsely claim Indigenous identity. Meanwhile, the use of Indigenous symbols and slogans has also grown increasingly common among the country’s far right.

Members of Kawartha Lakes First Nation argue they are exempt from laws and taxes, echoing the rhetoric of the extremist sovereign citizens movement, and the group’s emergence has raised concerns over how groups might use Indigenous identity to lay claim to land or demand concessions from local and provincial governments.

About two months ago, William Denby, the self-proclaimed “chief” of the Kawartha group began sending emails to local chiefs, municipal and provincial officials. The messages, seen by the Guardian, were often written in all caps and combined grievances and increasingly bold claims.

Read More Is a previously unheard-of First Nation just Canada’s latest Pretendian case? | Canada | The Guardian

Alberta Human Rights Commission 2022-2023 Annual Report

The Alberta Human Rights Commission has released its 2022-2023 Annual Report. The annual report provides a summary of the Commission’s activities from April 1, 2022 to March 31, 2023 and highlights the Commission’s key achievements towards advancing human rights in Alberta.

Below are some of the accomplishments you will find highlighted in the report.

In 2022-2023, the Commission:

Continued to resolve complaints effectively and efficiently and reached related goals:

This was the first full year that the new streamlined complaint management process was in effect. The streamlined complaint system uses specialized teams in intake, conciliation, and screening, while ensuring that parties have the opportunity to make their case.

For the fourth consecutive year, in 2022-23, the number of complaints closed exceeded the number of complaints accepted.

Through the work of our specialized teams, the average length of time from acceptance of a complaint until resolution, dismissal, or referral to Tribunal reduced to 515 days in 2022-23 from 538 days in 2021-2022 and 844 days in 2020-2021.

Hired a case manager to help self-represented parties navigate the Tribunal process and ensure an efficient process

Held a record number of tribunal hearings: The Tribunal held 32 tribunal hearings and published 142 written decisions on CanLII in section 26 appeals of Director decisions, interim decisions, and decisions on merits.

Began implementing our Indigenous Human Rights Strategy: This Strategy guides the Commission’s practices and initiatives with the goal of reducing barriers that Indigenous individuals and communities face. The Strategy is guided by an Indigenous Advisory Circle, made up of Indigenous individuals from all regions of the province who help support the Strategy’s implementation.

As part of the strategy, in 2022-2023, we conducted an organization wide external review to identify areas in which the Commission may be unknowingly perpetuating systemic discrimination against Indigenous Peoples through our programs, procedures, and operations.

With support from the Indigenous Advisory Circle, we began reviewing and implementing a number of the report's additional recommendations.

Moved forward on our project to rebuild the website: We conducted extensive stakeholder consultations—including 14 internal and external focus group sessions—to inform our new website, which launched in late 2023.

Launched the #AB50for50 campaign: The Commission used its 50th anniversary as an opportunity to engage Albertans human rights in action. Developed in consultation with community organizations, the #AB50for50 initiative encouraged Albertans to spend 50 minutes in 2023 expanding their knowledge and understanding of human rights.

Published the updated human rights guide, Human rights, pregnancy, and parental rights and responsibilities: The revised version reflects the 2015 and 2018 amendments to the Act, current case law, and Commission policies and guidelines.

Read the Commission’s 2022-2023 annual report for the complete listing of activities.

Below are some of the accomplishments you will find highlighted in the report.

In 2022-2023, the Commission:

Continued to resolve complaints effectively and efficiently and reached related goals:

This was the first full year that the new streamlined complaint management process was in effect. The streamlined complaint system uses specialized teams in intake, conciliation, and screening, while ensuring that parties have the opportunity to make their case.

For the fourth consecutive year, in 2022-23, the number of complaints closed exceeded the number of complaints accepted.

Through the work of our specialized teams, the average length of time from acceptance of a complaint until resolution, dismissal, or referral to Tribunal reduced to 515 days in 2022-23 from 538 days in 2021-2022 and 844 days in 2020-2021.

Hired a case manager to help self-represented parties navigate the Tribunal process and ensure an efficient process

Held a record number of tribunal hearings: The Tribunal held 32 tribunal hearings and published 142 written decisions on CanLII in section 26 appeals of Director decisions, interim decisions, and decisions on merits.

Began implementing our Indigenous Human Rights Strategy: This Strategy guides the Commission’s practices and initiatives with the goal of reducing barriers that Indigenous individuals and communities face. The Strategy is guided by an Indigenous Advisory Circle, made up of Indigenous individuals from all regions of the province who help support the Strategy’s implementation.

As part of the strategy, in 2022-2023, we conducted an organization wide external review to identify areas in which the Commission may be unknowingly perpetuating systemic discrimination against Indigenous Peoples through our programs, procedures, and operations.

With support from the Indigenous Advisory Circle, we began reviewing and implementing a number of the report's additional recommendations.

Moved forward on our project to rebuild the website: We conducted extensive stakeholder consultations—including 14 internal and external focus group sessions—to inform our new website, which launched in late 2023.

Launched the #AB50for50 campaign: The Commission used its 50th anniversary as an opportunity to engage Albertans human rights in action. Developed in consultation with community organizations, the #AB50for50 initiative encouraged Albertans to spend 50 minutes in 2023 expanding their knowledge and understanding of human rights.

Published the updated human rights guide, Human rights, pregnancy, and parental rights and responsibilities: The revised version reflects the 2015 and 2018 amendments to the Act, current case law, and Commission policies and guidelines.

Read the Commission’s 2022-2023 annual report for the complete listing of activities.

WHAT WAS REQUIRED TO CREATE A HISTORICAL TREATY?

March 7, 2024

By Bruce McIvor

A historical treaty between Indigenous Peoples and the Crown was created when each side intended to create legally binding obligations and their discussions were serious and dignified.

The Crown has a long history of denying the existence of historical treaties with Indigenous Peoples. With the change to the Indian Act in 1951 which removed the ban on First Nations hiring lawyers to defend their rights, Indigenous Peoples went to court to have their treaties recognized.

Their first major victory was the White and Bob British Columbia Court of Appeal decision in 1964. It confirmed the 1854 agreement between the Snuneymuxw and Governor Douglas of the Hudson’s Bay Company was a treaty and that the treaty rights still existed.

Later Supreme Court of Canada decisions further developed the law. Instead of relying on the international law of treaties, the Court developed its own principles based on a broad and liberal interpretation that wasn’t overly legalistic and considered the specific historical circumstances.

Over the objections of the Crown, the courts have confirmed the existence of various treaties including the Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1752 between the British and the Mi’kmaw (Simon, Marshall) and a one paragraph letter signed by British General Murrary in 1760 (shortly after the Battle of Quebec) guaranteeing rights to the Huron-Wendat (Sioui).

Regrettably, even when First Nations win court decisions confirming the existence of their treaties with the Crown, they continue to struggle to have the Crown respect their treaty rights, e.g. Mi’kmaw commercial fishing rights under the Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1752 (Marshall).

Read More What was required to create a historical treaty? (firstpeopleslaw.com)

The Crown has a long history of denying the existence of historical treaties with Indigenous Peoples. With the change to the Indian Act in 1951 which removed the ban on First Nations hiring lawyers to defend their rights, Indigenous Peoples went to court to have their treaties recognized.

Their first major victory was the White and Bob British Columbia Court of Appeal decision in 1964. It confirmed the 1854 agreement between the Snuneymuxw and Governor Douglas of the Hudson’s Bay Company was a treaty and that the treaty rights still existed.

Later Supreme Court of Canada decisions further developed the law. Instead of relying on the international law of treaties, the Court developed its own principles based on a broad and liberal interpretation that wasn’t overly legalistic and considered the specific historical circumstances.

Over the objections of the Crown, the courts have confirmed the existence of various treaties including the Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1752 between the British and the Mi’kmaw (Simon, Marshall) and a one paragraph letter signed by British General Murrary in 1760 (shortly after the Battle of Quebec) guaranteeing rights to the Huron-Wendat (Sioui).

Regrettably, even when First Nations win court decisions confirming the existence of their treaties with the Crown, they continue to struggle to have the Crown respect their treaty rights, e.g. Mi’kmaw commercial fishing rights under the Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1752 (Marshall).

Read More What was required to create a historical treaty? (firstpeopleslaw.com)

'Completely discouraged': Auditor slams First Nations housing, policing failures

OTTAWA — After two new reports detailing how the federal government is underperforming on First Nations housing and policing, the federal auditor general says a fundamental shift needs to occur in the government.

"Time after time, whether in housing, policing, safe drinking water or other critical areas, our audits of federal programs to support Canada's Indigenous Peoples reveal a distressing and persistent pattern of failure," Karen Hogan said at a press conference Tuesday.

"The lack of progress clearly demonstrates that the government's passive, siloed approach is ineffective, and, in fact, contradicts the spirit of true reconciliation."

The reports tabled in the House of Commons on Tuesday paint a bleak picture of Ottawa's record on First Nations housing and policing.

On First Nations housing, Hogan's report found little improvement to substandard over the past two decades.

And on the expansion of the highly criticized First Nations policing program, Hogan found poor management is leaving communities underserved and funds unspent.

Read More 'Completely discouraged': Auditor slams First Nations housing, policing failures - Business in Vancouver (biv.com)

"Time after time, whether in housing, policing, safe drinking water or other critical areas, our audits of federal programs to support Canada's Indigenous Peoples reveal a distressing and persistent pattern of failure," Karen Hogan said at a press conference Tuesday.

"The lack of progress clearly demonstrates that the government's passive, siloed approach is ineffective, and, in fact, contradicts the spirit of true reconciliation."

The reports tabled in the House of Commons on Tuesday paint a bleak picture of Ottawa's record on First Nations housing and policing.

On First Nations housing, Hogan's report found little improvement to substandard over the past two decades.

And on the expansion of the highly criticized First Nations policing program, Hogan found poor management is leaving communities underserved and funds unspent.

Read More 'Completely discouraged': Auditor slams First Nations housing, policing failures - Business in Vancouver (biv.com)

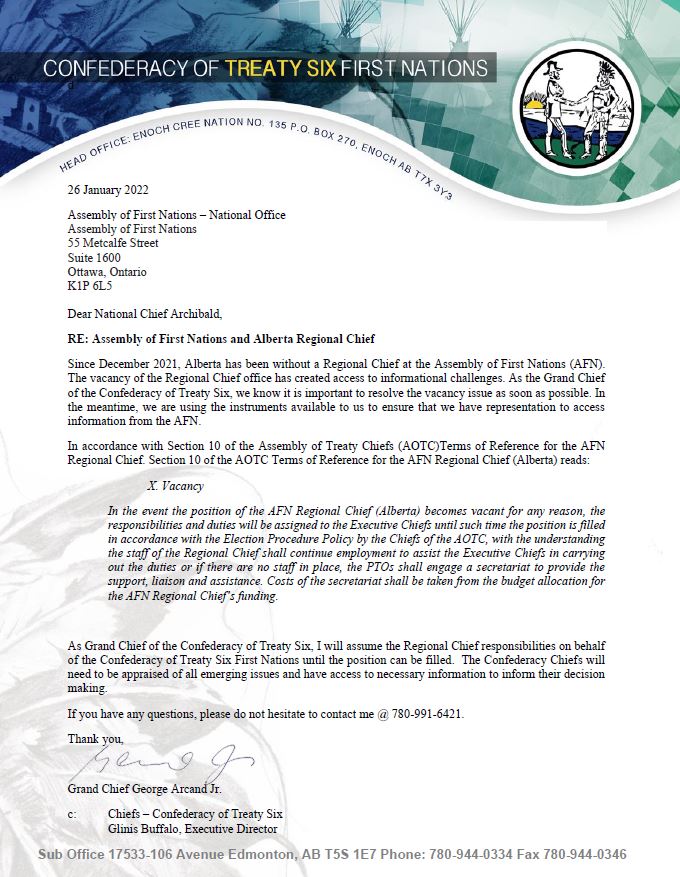

Treaty 6 creating a revenue sharing model for Alberta’s consideration

By Shari Narine

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

In July, the Confederacy of Treaty Six First Nations will begin creating a model for discussion with the province to share revenue from natural resource development

It’s a discussion that Alberta Premier Danielle Smith and her Cabinet ministers had with Treaty 6 chiefs last week just prior to the 2024-25 budget coming down, said Confederacy Grand Chief Cody Thomas.

“At the end of the day, (it’s) being at the table and coming up with solutions or creating the framework on how that revenue sharing can contribute to Indigenous and creating that model. The difference is we have a government willing to come to the table in a way we haven't seen before,” Thomas said.

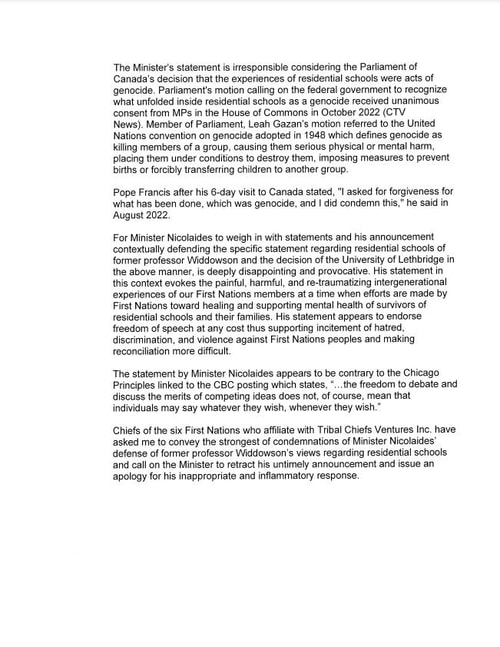

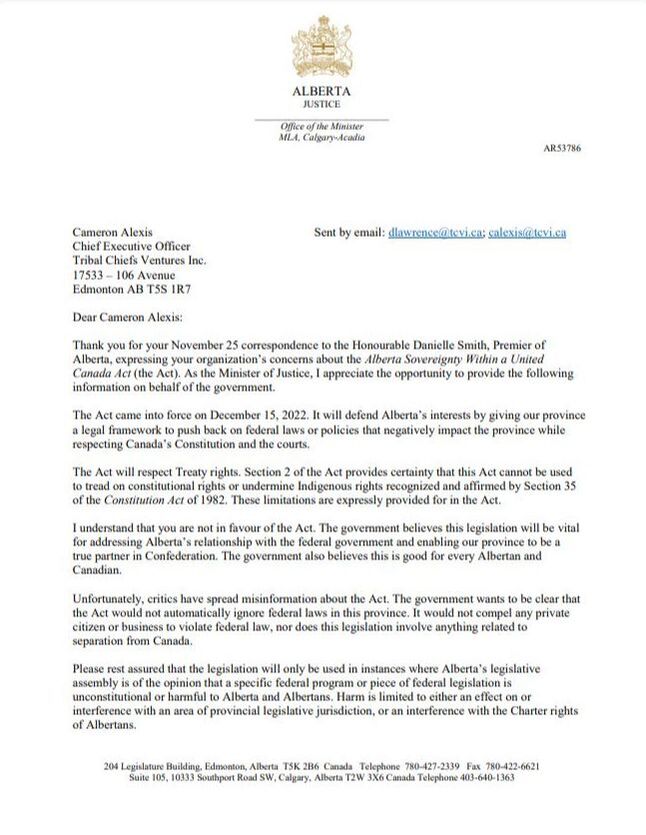

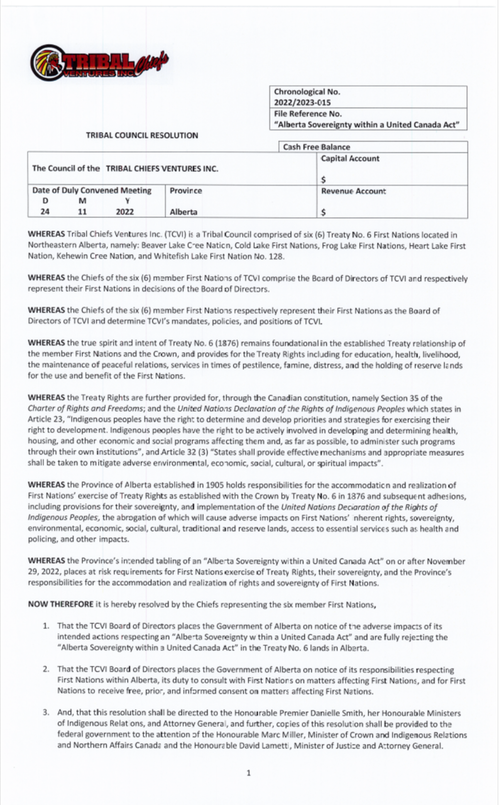

That’s a sharp contrast from what the Confederacy was saying just over a year ago when Smith’s first piece of legislation as new premier was the Alberta Sovereignty within a United Canada Act. The bill went through the legislature in December 2022 after government limited debate. Alberta chiefs viewed the act as a disregard of treaty and as a way for the province to gain access to lands without restrictions.

Read More Treaty 6 creating a revenue sharing model for Alberta’s consideration - Windspeaker.com

Local Journalism Initiative Reporter

Windspeaker.com

In July, the Confederacy of Treaty Six First Nations will begin creating a model for discussion with the province to share revenue from natural resource development

It’s a discussion that Alberta Premier Danielle Smith and her Cabinet ministers had with Treaty 6 chiefs last week just prior to the 2024-25 budget coming down, said Confederacy Grand Chief Cody Thomas.

“At the end of the day, (it’s) being at the table and coming up with solutions or creating the framework on how that revenue sharing can contribute to Indigenous and creating that model. The difference is we have a government willing to come to the table in a way we haven't seen before,” Thomas said.

That’s a sharp contrast from what the Confederacy was saying just over a year ago when Smith’s first piece of legislation as new premier was the Alberta Sovereignty within a United Canada Act. The bill went through the legislature in December 2022 after government limited debate. Alberta chiefs viewed the act as a disregard of treaty and as a way for the province to gain access to lands without restrictions.

Read More Treaty 6 creating a revenue sharing model for Alberta’s consideration - Windspeaker.com

Low emissions, Indigenous-owned Cascade Power Project to boost Alberta electrical grid reliability

New 900-megawatt natural gas-fired facility to supply more than eight per cent of Alberta's power needs

By Will Gibson on February 23, 2024, 11:34 am MST

Alberta’s electrical grid is about to get a boost in reliability from a major new natural gas-fired power plant owned in part by Indigenous communities.

Next month operations are scheduled to start at the Cascade Power Project, which will have enough capacity to supply more than eight per cent of Alberta’s energy needs.

It’s good news in a province where just over one month ago an emergency alert suddenly blared on cell phones and other electronic devices warning residents to immediately reduce electricity use to avoid outages.

“Living in an energy-rich province, we sometimes take electricity for granted,” says Chana Martineau, CEO of the Alberta Indigenous Opportunities Corporation (AIOC) and member of the Frog Lake First Nation.

“Given much of the province was dealing with -40C weather at the time, that alert was a vivid reminder of the importance of having a reliable electrical grid.”

Cascade Power was the first project to receive funding through the AIOC, the provincial corporation established in 2020 to provide loan guarantees for Indigenous groups seeking partnerships in major development projects.

Read More Low emissions, Indigenous-owned Cascade Power Project to boost Alberta electrical grid reliability (canadianenergycentre.ca)

Next month operations are scheduled to start at the Cascade Power Project, which will have enough capacity to supply more than eight per cent of Alberta’s energy needs.

It’s good news in a province where just over one month ago an emergency alert suddenly blared on cell phones and other electronic devices warning residents to immediately reduce electricity use to avoid outages.

“Living in an energy-rich province, we sometimes take electricity for granted,” says Chana Martineau, CEO of the Alberta Indigenous Opportunities Corporation (AIOC) and member of the Frog Lake First Nation.

“Given much of the province was dealing with -40C weather at the time, that alert was a vivid reminder of the importance of having a reliable electrical grid.”

Cascade Power was the first project to receive funding through the AIOC, the provincial corporation established in 2020 to provide loan guarantees for Indigenous groups seeking partnerships in major development projects.

Read More Low emissions, Indigenous-owned Cascade Power Project to boost Alberta electrical grid reliability (canadianenergycentre.ca)

First Peoples Law Report for January 9th

In case you missed it, check out our 2023 Indigenous Rights Year in Review.

2023 Indigenous Rights Year in Review | First Peoples Law

This week’s edition includes (lack of) progress on the Calls to Action, economic reconciliation, fishing, mining and more.

You can read it on our website here.

IN THE NEWS

National news featured the Calls to Action, Métis rights, Ribbon Skirt day and mining

Calls to Action Accountability: A 2023 Status Update on Reconciliation | Yellowhead Institute

With belaboured bill recognizing Métis self-government in limbo, here's what to know | St Albert Gazette

Ribbon Skirt day a reminder there's much work to be done | Winnipeg Sun

Consulting Indigenous communities on critical minerals is key to net zero ambitions | The Globe and Mail*

Fishing rights and Indigenous identity were the top stories on the East Coast

Fishery court cases roundup: Jan. 2-5, 2024 | Ku'ku'kwes News

Indigenous faculty raise concerns about Dalhousie University's proposed identification process | CBC News

Quebec news included day schools and consultation

Class action seeks compensation for Indigenous day school survivors in Quebec | CBC News

Hydro-Quebec is touting 'economic reconciliation' | APTN News

Ontario headlines highlighted mining, economic reconciliation and policing

Ontario chiefs seek halt to online mining claim-staking | Northern Ontario Business

Tragic Death of Indigenous Woman Sparks Discussions on Policing and Indigenous Rights | NetNewsLedger

Rama First Nation takes ownership of 5 Ramara roads | Simcoe.com

For Marten Falls First Nation, economic reconciliation begins and ends in the Ring of Fire | The Globe and Mail*

Treaty rights returned to the news in Manitoba

First Nations hunters aim to change provincial restrictions | Winnipeg Sun

Harvesting rights and cumulative impacts were front and centre in the North

Board recommends against proposed mining road in central Yukon | Eye on the Arctic

BC headlines included fishing, Land Back, UNDRIP and conservation

Feds must fix unfair West Coast fishing rules: House committee | Penticton Herald

First Nation appeals court decision | CIM Magazine

Marina gets new name amid transition to First Nation | Victoria Times Colonist

Canada’s Nature Agreement underscores the need for true reconciliation with Indigenous nations | The Conversation

Colville Confederated Tribes are bringing Canada lynx home | The Narwhal

FROM THE COURTS

The Yukon Supreme Court weighed in on consultation for the Kudz Ze Kayah mine project

Ross River Dena Council v Yukon (Government of), 2024 YKSC 1

Court hands partial victory to First Nations who say they weren't properly consulted over Yukon mine project | CBC News

QUOTE OF THE WEEK

“You should not have to be arrested by conservation officers or have game confiscated by conservation officers for exercising your protected and inherent rights, rights that are constitutionally protected.”

- Grand Chief Garrison Settee, Manitoba Keewatinowi Okimakanak

OFF THE BOOKSHELF

"There is room on this land for all of us and there must also be, after centuries of struggle, room for justice for Indigenous peoples. That is all we ask. And we will settle for nothing less.”

- Arthur Manuel, Unsettling Canada: A National Wake-Up Call (2021)

*Article is paywalled and may require a subscription to access.

January 2024National Coaches Coaching Certification Program (NCCP) UpdatesHappy New Year! The February and March NCCP multi-sport schedule has been posted on the NCCP multi-sport calendar. Register early as these modules will fill up quickly.

The NCCP Advanced Coaching Diploma (ACD) helps Competition Development Certified or Trained coaches prepare for podium success at the Provincial, National and International Level. This one-year program allows coaches to connect and learn from experienced mentors, content experts, fellow coaches, and respected sport partners across Canada. Application deadline for the Canadian Sport Institute – Calgary cohort is January 31.

For more information on the Advanced Coaching Diploma, contact CSI – Calgary or register through the Locker.

Winter Walk Day - February 7, 2024February is almost here and that means Winter Walk Day is quickly approaching. Winter Walk Day is a great opportunity to be active and have fun with your family, friends, and colleagues. All Albertans can embrace the Winter Walk Day spirit by putting on their boots and warm clothes and enjoying a 15-minute walk or outdoor activity on Wednesday, February 7.

Remember, you do not have to wait for Winter Walk Day to be active! Any day can be an active day - just open the door and go for it. Staying active during the winter is important to maintaining a healthy lifestyle. In fact, research shows that spending time outdoors and being active benefits both mental and physical well-being.

Outdoor physical activity is a great social opportunity too. Join a group of friends, co-workers, or students, and register for 2024 Winter Walk Day with Safe Healthy Active People Everywhere (SHAPE).

Get outside and enjoy the fresh air - celebrate your mental and physical well-being by taking time for an enjoyable winter walk! Don’t forget to tag @SHAPE_Alberta and add #WinterWalkDay to your posts!

2023 Alberta Sport Recognition Awards - Nomination Deadline January 15, 2024Have you nominated a deserving athlete, team, coach, or technical official for an Alberta Sport Award yet? The deadline is right around the corner – January 15! Since 2002, the Alberta Sport Recognition Awards have been presented to honor the extraordinary athletic accomplishments of our high-performance Alberta athletes, teams, coaches, and officials.

Please go to the Alberta Sport Recognition Award webpage for a list of awards and nomination guidelines.

Major Cultural and Sport Events Grant (MCSE)Did you know the Ministry of Tourism and Sport now administers the Major Cultural and Sport Events (MCSE) grant program?

Applications and guidelines are currently under review and will be available on the SPAR website in early 2024.

For more information please go to the SPAR Website.

2026 Alberta Summer Games Community AnnouncementCongratulations to Strathcona County, chosen to host the 25th Alberta Summer Games in 2026!

The Summer Games have been a part of the sport community in Alberta for almost 50 years, bringing young athletes ages 11-16 together to compete in a variety of sports.

An $820,000 operating grant will be provided to the host society to support the 2026 event, which generated about $9 million in economic impact for the host community at the most recent Alberta Summer Games in Okotoks.

Strathcona County previously hosted the 1987 Alberta Summer Games and the 2000 Alberta Winter Games.

Please go to the Summer Games Website for more information.

ParticipACTION Community ChallengeThe Community Challenge is coming back in June 2024! Even though it is still a few months away, it is not too early to contact your municipality and spread the word so that your community has the best chance of being named Canada’s Most Active Community and winning $100,000 to support local sport and physical activity initiatives!

Community organizations are encouraged to apply for grants of up to $1,500 from January 16 to February 13. The grants can be used for staffing, training, promotion, equipment, and venue rentals. They are designed to increase sport and physical activity participation.

Everyone should have the opportunity to enjoy the mental and physical benefits of being active, including the essential feeling of inclusion and belonging to a community.

Go to the ParticipACTION website for more information.

The 2024 Alberta Winter Games - February 16-19, 2024 - Grande Prairie, AlbertaThe countdown is on for Alberta’s athletes, coaches and technical officials who will travel to Grande Prairie for the 2024 Alberta Winter Games.

Over 2,800 participants will represent eight zones from across the province in 19 different sports. The Opening Ceremonies will take place on February 16. We are excited to see who will light the Alberta Games Cauldron to start the games.

Go to the Alberta Winter Games Website for more details. Good Luck to everyone as you prepare to compete at the games!

Non Profit WebinarsThe Government of Alberta’s Community Development Unit (CDU) is offering free webinars in grant writing, board development, governance, role of the board executives, and other courses for non-profits. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

Alberta Association of Recreation Facility Personnel Conference (AARFP) - April 21-24, LethbridgeThe Alberta Association of Recreation Facility Personnel (AARFP) annual conference and tradeshow will take place next Spring in Lethbridge. The theme for this year’s conference is “The Bridge to Recreation”.

The event is designed for all recreation managers, directors, operators, coordinators, supervisor, administrative assistants, and all professionals who want to strengthen our recreation community.

Registration is now open. Please go to the conference web page for more details.

The NCCP Advanced Coaching Diploma (ACD) helps Competition Development Certified or Trained coaches prepare for podium success at the Provincial, National and International Level. This one-year program allows coaches to connect and learn from experienced mentors, content experts, fellow coaches, and respected sport partners across Canada. Application deadline for the Canadian Sport Institute – Calgary cohort is January 31.

For more information on the Advanced Coaching Diploma, contact CSI – Calgary or register through the Locker.

Winter Walk Day - February 7, 2024February is almost here and that means Winter Walk Day is quickly approaching. Winter Walk Day is a great opportunity to be active and have fun with your family, friends, and colleagues. All Albertans can embrace the Winter Walk Day spirit by putting on their boots and warm clothes and enjoying a 15-minute walk or outdoor activity on Wednesday, February 7.

Remember, you do not have to wait for Winter Walk Day to be active! Any day can be an active day - just open the door and go for it. Staying active during the winter is important to maintaining a healthy lifestyle. In fact, research shows that spending time outdoors and being active benefits both mental and physical well-being.

Outdoor physical activity is a great social opportunity too. Join a group of friends, co-workers, or students, and register for 2024 Winter Walk Day with Safe Healthy Active People Everywhere (SHAPE).

Get outside and enjoy the fresh air - celebrate your mental and physical well-being by taking time for an enjoyable winter walk! Don’t forget to tag @SHAPE_Alberta and add #WinterWalkDay to your posts!

2023 Alberta Sport Recognition Awards - Nomination Deadline January 15, 2024Have you nominated a deserving athlete, team, coach, or technical official for an Alberta Sport Award yet? The deadline is right around the corner – January 15! Since 2002, the Alberta Sport Recognition Awards have been presented to honor the extraordinary athletic accomplishments of our high-performance Alberta athletes, teams, coaches, and officials.

Please go to the Alberta Sport Recognition Award webpage for a list of awards and nomination guidelines.

Major Cultural and Sport Events Grant (MCSE)Did you know the Ministry of Tourism and Sport now administers the Major Cultural and Sport Events (MCSE) grant program?

Applications and guidelines are currently under review and will be available on the SPAR website in early 2024.

For more information please go to the SPAR Website.

2026 Alberta Summer Games Community AnnouncementCongratulations to Strathcona County, chosen to host the 25th Alberta Summer Games in 2026!

The Summer Games have been a part of the sport community in Alberta for almost 50 years, bringing young athletes ages 11-16 together to compete in a variety of sports.

An $820,000 operating grant will be provided to the host society to support the 2026 event, which generated about $9 million in economic impact for the host community at the most recent Alberta Summer Games in Okotoks.

Strathcona County previously hosted the 1987 Alberta Summer Games and the 2000 Alberta Winter Games.

Please go to the Summer Games Website for more information.

ParticipACTION Community ChallengeThe Community Challenge is coming back in June 2024! Even though it is still a few months away, it is not too early to contact your municipality and spread the word so that your community has the best chance of being named Canada’s Most Active Community and winning $100,000 to support local sport and physical activity initiatives!

Community organizations are encouraged to apply for grants of up to $1,500 from January 16 to February 13. The grants can be used for staffing, training, promotion, equipment, and venue rentals. They are designed to increase sport and physical activity participation.

Everyone should have the opportunity to enjoy the mental and physical benefits of being active, including the essential feeling of inclusion and belonging to a community.

Go to the ParticipACTION website for more information.

The 2024 Alberta Winter Games - February 16-19, 2024 - Grande Prairie, AlbertaThe countdown is on for Alberta’s athletes, coaches and technical officials who will travel to Grande Prairie for the 2024 Alberta Winter Games.

Over 2,800 participants will represent eight zones from across the province in 19 different sports. The Opening Ceremonies will take place on February 16. We are excited to see who will light the Alberta Games Cauldron to start the games.

Go to the Alberta Winter Games Website for more details. Good Luck to everyone as you prepare to compete at the games!

Non Profit WebinarsThe Government of Alberta’s Community Development Unit (CDU) is offering free webinars in grant writing, board development, governance, role of the board executives, and other courses for non-profits. ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏ ͏

- Building Consensus (**New webinar)

- Board Development Program

- Building Strong Teams and Effective Relationships

- Connect with Donors this Giving Season - A Crowdfunding Alberta Webinar (**New webinar)

- Grant Writing 101

- Community Facility Enhancement Program (CFEP) Small - Morning and Afternoon Session

- Community Initiatives Program (CIP) Project-Based - Morning and Afternoon Session

- Community Initiatives Program (CIP) Operating Stream - Program Information

- Cultural Heritage Initiatives Program (CHIP) - Program Information

- How to Submit a CIP Operating Application Through Front Office

Alberta Association of Recreation Facility Personnel Conference (AARFP) - April 21-24, LethbridgeThe Alberta Association of Recreation Facility Personnel (AARFP) annual conference and tradeshow will take place next Spring in Lethbridge. The theme for this year’s conference is “The Bridge to Recreation”.

The event is designed for all recreation managers, directors, operators, coordinators, supervisor, administrative assistants, and all professionals who want to strengthen our recreation community.

Registration is now open. Please go to the conference web page for more details.

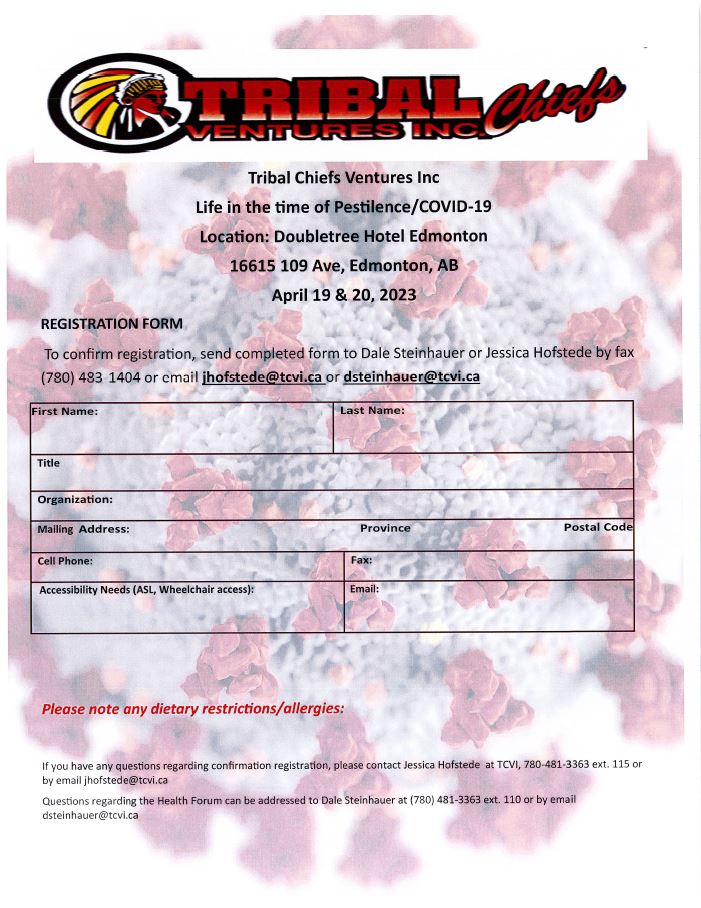

Tribal Chiefs Ventures Inc. has completed a project to better understand climate resilience in our member First Nations. This project was funded by the Government of Alberta, through the Municipal Climate Change Action Centre’s Climate Resilience Capacity Building Program. The Municipal Climate Change Action Centre (MCCAC) is a partnership of Alberta Municipalities, Rural Municipalities of Alberta, and the Government of Alberta. For questions, contact [email protected].

Did you know the Alberta Human Rights Commission has launched a new website? With mobile-friendly features and revised content, their new website aims to enhance the user experience and improve accessibility. New features also aim to improve the value of the website as a trusted tool for human rights education in Alberta.

Visit the new website to learn more: https://albertahumanrights.ab.ca/

Visit the new website to learn more: https://albertahumanrights.ab.ca/

Indigenous Rookie League wraps up for the season

The Indigenous Rookie League, supported by the Jays Care Foundation and Tribal Chiefs Ventures Inc., included six area First Nations communities. LAKELAND - The Indigenous Rookie League, supported by the Jays Care Foundation and Tribal Chiefs Ventures Inc., included six area First Nations communities.

Read More Indigenous Rookie League wraps up for the season - LakelandToday.ca

Read More Indigenous Rookie League wraps up for the season - LakelandToday.ca

'Forever chemicals' found in Canadians' blood samples: report

|

Government departments propose listing the chemicals as toxic under Canadian Environmental Protection Act

Toxic "forever chemicals" are being found in the blood of Canadians — and even higher levels are being found in northern Indigenous communities — says a new report from the government of Canada. Health Canada and Environment Canada have released a draft assessment of the science on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Both departments propose listing the human-made chemicals as toxic under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA). Canadians have until mid-July to weigh in on the proposed change. David Thurton · CBC · Posted: May 20, 2023 2:00 AM MDT |

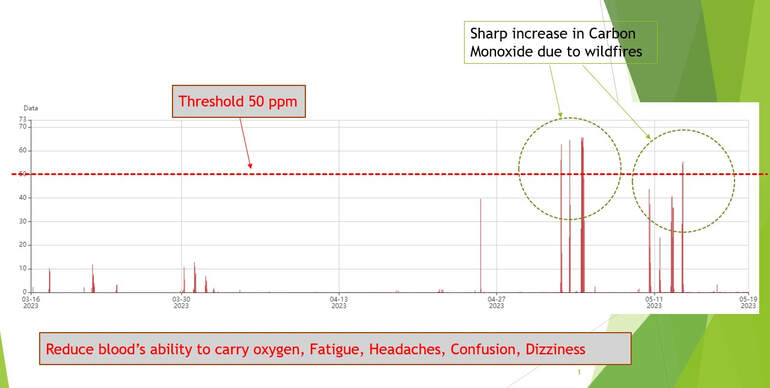

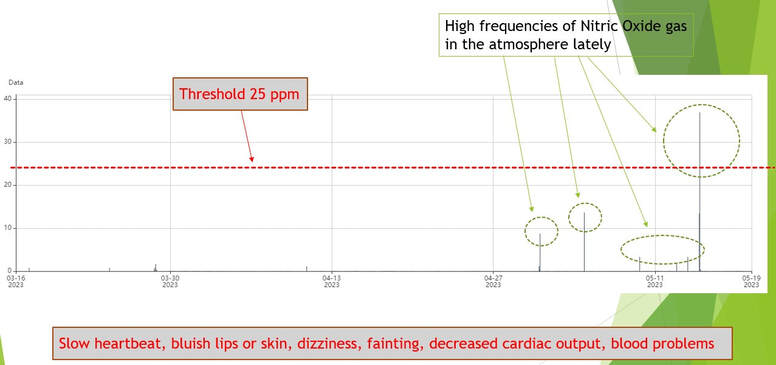

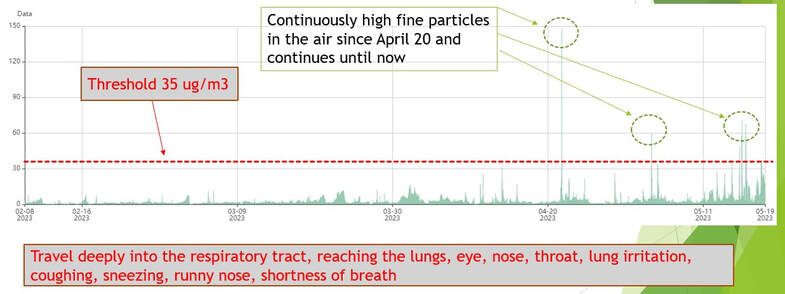

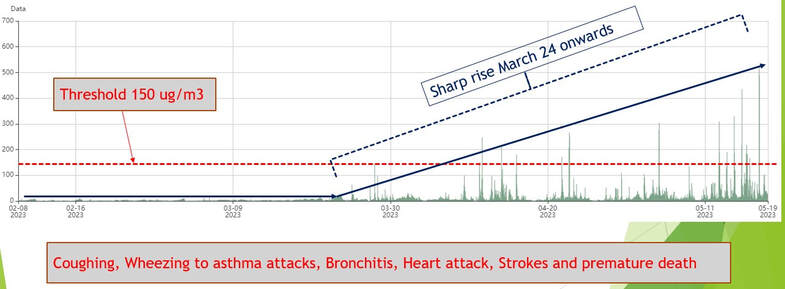

Air Quality in Whitefish

Carbon Monoxide:

Nitric Oxide:

Fine dust particles in the air (PM2.5):

Coarse dust particles in the air (PM10):

At a Glance - May 12, 2023

Wildfires Continue

Alberta declared a state of emergency this week as wildfires continue to burn. While the cooler weather offered a slight respite, allowing several thousand evacuees to return home, conditions are expected to worsen as the weather becomes hotter and drier ahead of the weekend. Temperatures are projected to be fifteen degrees above what is typical for May as Alberta enters a heat dome expected to last Friday to Tuesday. As the effort to fight the blaze continues, firefighters question budget-cuts that have left the province battling the wildfire short-handed. A former Alberta-based elite firefighter group feel that they “could have been difference-makers” had the UCP not cut the program in 2019. This week, the provincial government announced that evacuees that have been displaced for seven-days will be eligible for compensation. Eligible adults will receive a one-time payment of $1,250 and an additional $500 will be available for each dependent child under 18. For a family of four, this would amount to $3,500 total. The province also provided clarification that the seven-days need not be consecutive in order to be eligible for compensation.

Controversies of the Week

Danielle Smith has found herself embroiled in several new – and renewed – controversies this week. A resurfaced video of Danielle Smith, captures her comparing 75% of vaccinated Albertans to Nazi Supporters. Smith apologized and attributed her comments to the pandemic, citing that it was a “difficult and frustrating time for everyone.” Her apology was not well received by several groups, notably the Jewish Human Rights group - B’nai Brith Canada - and the Royal Canadian Legion. Additionally, Smith has come under fire this week for informing UCP supporters at a party event about the Alberta government’s impending announcement of a state of emergency prior to informing the public. Smith’s spokesman has so far declined to address questions over the disclosure.

Safe Streets Campaign Promise

In one of their most recent campaign promises, and days after the fatal stabbing of a mother and daughter in the Mill Woods community, the UCP has announced their plan to restore safety to city-streets and public-transit safer if re-elected. At a press conference, Smith and Mike Ellis announced several measures that will be taken in order to accomplish this, including ankle bracelets for dangerous offenders out on bail, an anti-fentanyl and anti gun trafficking teams, and increased funding to address gang-related crime and child exploitation. The UCP also announced this week that they plan to provide more funding for women’s shelters and sexual assault counselling. Regarding the UCP’s stated intention to impose ankle bracelets to monitor offenders out on bail, several experts have raised their concerns about the legality, and feasibility, of such a promise. Many have raised their concern that due to the separation of powers between the judicial system and the government, the provincial government would have no authority to enforce a promise such as this.

NDP Deny Accusations of Illegal Third-Party Advertising

The UCP addressed a letter written by the executive director of the party on May 2nd to Elections Alberta disclosing their concern that three unions have been involved in third-party advertising to benefit the Alberta NDP leader Rachel Notley as well as “colluding” with the NDP to exceed contribution and expense limits while failing to submit proper financial reports. The three unions of concern are the Federation of Labour, Canadian Union of Public Employees and Alberta Teachers Union. While all unions and the Alberta NDP have released statements dismissing the concerns raised by the UCP as baseless, it will be up to Elections Alberta to ensure there have been no compliance failures and launch an investigation if they see fit.

Sask. journalist wins Pulitzer Prize, Peabody for podcast about her father's residential school experience

|

Connie Walker and team at Spotify's Gimlet Media win best audio journalism for Stolen: Surviving St. Michael's

A Saskatchewan First Nations woman's story about her father's residential school experience has won the Pulitzer Prize and a Peabody Award in the span of 24 hours. Stolen: Surviving St. Michael's, a podcast by journalist Connie Walker and the team at Spotify's Gimlet Media, won the 2023 Pulitzer Prize on Monday for best audio journalism. The following day, it won a Peabody Award for its "its tenacious reporting and continued commitment to recognizing the full history of the Indigenous community" in the podcast and radio category. "I feel like I'm still in shock. It's disbelief. It means so much. It's an incredible honour," Walker said Monday. CBC News · Posted: May 08, 2023 5:02 PM MDT |

|

This week’s edition includes Treaty rights, court cases, legal personhood, UNDRIP and more. You can read it on our website here.

IN THE NEWS

Treaty rights were front and centre on the east coast

Legal personhood was in the spotlight in Quebec

Ontario news included Treaty rights, jurisdiction and consultation

UNDRIP, Treaty rights and cannabis laws topped BC headlines

UNDRIP also featured in NWT news

FROM THE COURTS

Here’s a new case out of BC regarding possession of reserve lands

IN THE NEWS

Treaty rights were front and centre on the east coast

Legal personhood was in the spotlight in Quebec

- First Nations chiefs adopt resolution declaring St. Lawrence River a legal person | iHeartRadio

- AFN leader pitches ‘personhood’ status for St. Lawrence River | APTN News

- The Legal Personhood of the St. Lawrence River Recognized and Presented by First Nations to the UN | AFNQL

Ontario news included Treaty rights, jurisdiction and consultation

- Treaty 9 nations suing Canada, Ontario over jurisdiction | APTN News

- First Nations sue over Treaty 9, raising questions on Ring of Fire | The Narwhal

- Without First Nations’ consent mining critical minerals is cultural genocide, leader tells Ontario, Canada | Wind Speaker

- Atikameksheng Anishnawbek issues a formal response to Ontario government’s proposed Bill 71, Building More Mines Act | Anishinabek News

- Changes to Mining Act expose cracks in Ontario's duty to consult with First Nations | CBC News

UNDRIP, Treaty rights and cannabis laws topped BC headlines

- $200M UNDRIP fund will empower First Nations in B.C., Indigenous leaders say | Global News

- Local First Nations' loss of Montney Reserve ignites 20-year legal battle for justice | Energetic City

- Cannabis laws in B.C. need changing say First Nation Leaders | APTN news

- New agreements between First Nations and B.C. government a step toward fulfilling Canada's treaty obligations | The Conversation

UNDRIP also featured in NWT news

- Dehcho First Nations' support of UNDRIP legislation 'up in the air': grand chief | CKLB Radio

- UNDRIP implementation not supported by all Indigenous governments in the N.W.T. | CBC News

FROM THE COURTS

Here’s a new case out of BC regarding possession of reserve lands

Kainai Blood Tribe has a drug problem ‘with no antidote’ says doctor

|

A physician on the Kainai Blood Tribe in southern Alberta says the community has a drug problem is killing people and has no antidote.

“Xylazine will be a problem across the province and people are dying within ten minutes of taking it,” says Dr. Esther Tailfeathers. Tailfeathers says the number of young people dying from it are chilling. Kainai Blood Tribe in throes of Xylazine Fentanyl epidemic (aptnnews.ca) |

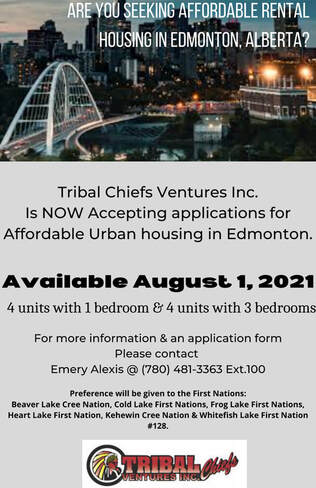

Today, Statistics Canada released "Study: Housing experiences and well-being among First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit, 2018".

Housing experiences and measures of health and well-being among First Nations people living off reserve, Métis and Inuit: Findings from the 2018 Canadian Housing Survey (statcan.gc.ca)

As a key social determinant of health, housing tenure and conditions can have profound impacts on well-being. Indigenous people are disproportionately affected by inadequate, unaffordable, and unsuitable housing as findings from a newly released study on housing experiences and well-being indicate.

Using the 2018 Canadian Housing Survey, a unique dataset that combines housing and well-being indicators, this study examines previously explored housing measures (e.g., living in crowded dwellings or those in need of major repairs) in addition to new ones in relation to health, life satisfaction, and financial hardship offering a more fulsome picture of housing and well-being among Indigenous people. Given the nature of the survey's data collection, the findings of this study are reflective of responses obtained from Indigenous housing decision-makers aged 15 and older (known as reference persons) within their household with estimates presented for Indigenous households and people within those households where relevant. Findings exclude people living on reserve.

ISCDI Training:

The Indigenous Statistical Capacity Development Initiative (ISCDI) is offering the training sessions. See calendar below.

As a key social determinant of health, housing tenure and conditions can have profound impacts on well-being. Indigenous people are disproportionately affected by inadequate, unaffordable, and unsuitable housing as findings from a newly released study on housing experiences and well-being indicate.

Using the 2018 Canadian Housing Survey, a unique dataset that combines housing and well-being indicators, this study examines previously explored housing measures (e.g., living in crowded dwellings or those in need of major repairs) in addition to new ones in relation to health, life satisfaction, and financial hardship offering a more fulsome picture of housing and well-being among Indigenous people. Given the nature of the survey's data collection, the findings of this study are reflective of responses obtained from Indigenous housing decision-makers aged 15 and older (known as reference persons) within their household with estimates presented for Indigenous households and people within those households where relevant. Findings exclude people living on reserve.

ISCDI Training:

The Indigenous Statistical Capacity Development Initiative (ISCDI) is offering the training sessions. See calendar below.

Date |

Workshop |

April 25-26, 2023 1:00-3:30pm (ET) |

Using Indigenous data from the 2021 Census (2 half-day course offered in English) Conducted every five years, the Census of Population is the most comprehensive source of data on the demographic, social and economic characteristics of Canadians. This course will explore the 2021 Census of Population data available and enhance participants’ ability to use data to support their community and organization’s needs. This course will provide participants with a basic understanding of the methodology and processes involved in conducting the census, and will explore census geographies, universes and variables used within the census with a focus on the Indigenous population. This course will also demonstrate how to use Census Program website tools and how to find and use census data on the Statistics Canada Website. |

May 2-3, 2023 1:00-3:00pm (ET) |

Introduction to Statistics (2 half-day course offered in English) This course will provide participants with a basic understanding of statistics, including key statistical concepts, how data can be interpreted using statistics, and how statistics can help to understand a particular topic of interest. The course will also discuss how descriptive statistics, including averages and distributions are calculated and interpreted |

May 4, 2023 1:00-2:30pm (ET) |

Navigating the Statistics Canada Website (offered in English) This course is an introduction to the Statistics Canada website. The course will guide participants through the main sections of the website, focusing on how to access Indigenous statistics as well as how to find key indicators, community-level data, and census data products. |

May 9-10, 2023 1:00-2:30pm (ET) |

Preparing Funding Proposals (2 half-day course offered in English) This course will discuss different components of funding proposals, including developing an idea into a plan, identifying potential funding opportunities, finding the data needed to support the proposal, and how to write the proposal using the data identified. |

May 16-18, 2023 1:00-3:00pm (ET) |

Surveys from Start to Finish (3 half-day course offered in English) This course will provide participants with the basic knowledge needed to understand and evaluate surveys by walking through the steps of the survey process. Topics include questionnaire design, data collection methods, working with the data collected and communicating the results in an accessible way. |

June 1, 2023 1:00-2:30pm (ET) |

Navigating the Statistics Canada Website (offered in French) This course is an introduction to the Statistics Canada website. The course will guide participants through the main sections of the website, focusing on how to access Indigenous statistics as well as how to find key indicators, community-level data, and census data products. |

June 14-15, 2023 1:00-3:00pm (ET) |

Preparing Funding Proposals (2 half-day course offered in French) This course will discuss different components of funding proposals, including developing an idea into a plan, identifying potential funding opportunities, finding the data needed to support the proposal, and how to write the proposal using the data identified. |

The Indigenous Statistical Capacity Development Initiative enables Indigenous organizations and communities to develop statistical capacity to increase self-determination by providing training on various topics as they relate to statistics. *Please note that the ISCDI courses are offered at no cost to Indigenous communities and members from Indigenous organizations.

To register or for more information, please email: [email protected]

To register or for more information, please email: [email protected]

|

|

Job opportunity at PrairiesCanPlease see below the link to the CO-02 (Senior Business Officer ) The immediate vacancy will require supporting Alberta Indigenous communities to pursue economic development projects that either increase energy efficiency in communities or increases clean energy generation. Career Opportunity: The following job opportunity is available in the following locations: Calgary (Alberta), Edmonton (Alberta), Fort McMurray (Alberta), Grande Prairie (Alberta), Lethbridge (Alberta). The job opportunity can be accessed with the following link: Senior Business Officer (cfp-psc.gc.ca) |

Empowering Indigenous Learners CPAWSB and AFOA Alberta Collaborate on Tailored CPA Certification Program OfferingsWe're excited to share that the CPA Western School of Business (CPAWSB) and the Aboriginal Financial Officers Association of Alberta (AFOA) have joined forces to create two courses for Indigenous learners. These courses are based on the regular CPA certification program but will be tailored to meet the unique preferences and expectations of Indigenous learners and incorporate Indigenous culture and context in the program.

|

Ontario says it doesn’t owe First Nations seeking compensation for broken treaty

Sean Fine Justice Writer

Indigenous communities are in court seeking billions of dollars in compensation after almost 150 years of receiving small annual payments in return for ceding an area the size of France. But the Ontario government is arguing they are owed nothing, or at most $34-million.

The wide divergence in claims was on display this week in an unprecedented court hearing in Sudbury, Ont., whose purpose is to determine how much the Crown owes for breaking a treaty promise to share wealth produced by the natural resources of a vast area in Northern Ontario.

A lawyer for several Anishinaabe communities collectively made up of about 15,000 people told Ontario Superior Court Justice Patricia Hennessy on Monday that they are owed at least $8-billion, and perhaps as much as $100-billion.

In 1850, Anishinaabe leaders signed two treaties with the Crown that gave over control of resource-rich lands stretching from the north shores of Lake Superior and Lake Huron to Hudson Bay, which today includes the communities of Thunder Bay, Sault Ste. Marie, Sudbury and North Bay.

But the Crown, after paying an initial lump sum of a few thousand dollars, has been making annuity payments capped at just $4 a person since 1875.

Justice Hennessy will be devising a revenue-sharing plan to compensate for the past resource wealth generated on these treaty lands. It will be the first such court-ordered plan in Canada, and it will have enormous practical consequences for thousands of Anishinaabe people in Northern Ontario, who courts have said were left impoverished by the Crown’s neglect of its treaty promise.

Five years ago, Justice Hennessey ruled that the Crown had broken a pledge, set out in two 1850 treaties, to augment the annuity payments as Crown resource revenues permitted. In 2021, the Ontario Court of Appeal largely upheld her ruling.

The judge now has a monumental task: she must determine what revenues to count, what expenses to subtract from those revenues, what interest rate should apply to reflect growth over time and what share of the net revenues should be paid to the First Nations involved.

And on top of all that, she needs to decide which level of government – federal, or provincial – is on the hook for the money owed. On Tuesday, federal lawyer Glynis Evans told Justice Hennessy the vast majority is owed by Ontario. On Wednesday, Ontario’s lawyer, Tamara Barclay, said all of it is owed by the federal government. She added that Supreme Court rulings of the late 19th century had resolved the issue.

But the complications do not end there. Even as four months of hearings got under way this week in a large, makeshift courtroom in Sudbury, the province is still appealing the Ontario Court of Appeal’s earlier ruling on whether the Crown actually did break its treaty promise to share the wealth. That case is pending at the Supreme Court of Canada.

If the Supreme Court overturns that ruling, the entire exercise in Sudbury would be for naught. But given that the First Nations’ lawsuit over the treaty promise began in 1999, and that Anishinaabe elders knowledgeable in oral history and cultural matters are not getting any younger, the Supreme Court rejected Ontario’s request for a stay of the compensation hearings. So did Justice Hennessy.

The First Nations who are parties to the case have shifted. The Red Rock and Whitesand First Nations, who are part of the Robinson-Superior Treaty, have been joined by three other First Nations. Another seven First Nations say they never gave over title to their lands and are trying to win court recognition of that claim (though not as part of the current case). They are represented at the hearings in case they do not ultimately establish that they have title.

Another 21 First Nations are part of the Robinson-Huron Treaty, a territory also addressed by the initial court rulings. This group is now in negotiations with the two levels of government. Their compensation hearing has been adjourned indefinitely.

Harley Schachter, a lawyer representing Red Rock, Whitesand and three other First Nations, likened Ontario’s position that governments owe virtually nothing to that of a fox left in charge of the chickens.

“The fox turns to the judge – got egg all over his face – and in the most reassuring manner and calm tone he can muster says, ‘Look, judge, firstly, about the eggs, there are none, so I don’t know why the chickens are complaining,’” he told Justice Hennessy on Monday, the first day of the hearings.

His clients are claiming an 84-per-cent share of net Crown revenues in five areas, including mining and forestry. The 84 per cent is based on the share of economic risk the First Nations say they took on in the joint venture represented by the treaty.

The higher estimates in the tens of billions of dollars reflect not just what the Crown recouped in various fees, but the higher fees it could have charged if its aim had been to collect on their full value. (Mr. Schachter called this approach “economic rents.”)

On Friday, two-time Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz, an economist, will testify in support of that approach.

“Yes, the final amounts claimed as payable are large,” Mr. Schachter told Justice Hennessy. “They are large because the Crowns did not honour the treaty obligation. They are large but they are not untoward.”

Ms. Barclay, representing Ontario, told Justice Hennessy the province lost $7.9-billion on resources in the territory.

That figure includes the costs of building roads and railways. An alternative approach to determining net revenues would mean $34-million is owed to the Anishinaabe, she said. The First Nations argue that road and railway costs are part of nation-building and should not be deducted from revenues.

Ms. Evans, representing the federal government, said Tuesday the Anishinaabe’s share of net Crown revenues should be roughly 10 per cent, reflecting the ratio of Indigenous to non-Indigenous people in the Robinson-Superior treaty territory. She did not put forward a precise dollar figure, but opposed the “economic rents” approach of the First Nations.

Sean Fine Justice Writer

Indigenous communities are in court seeking billions of dollars in compensation after almost 150 years of receiving small annual payments in return for ceding an area the size of France. But the Ontario government is arguing they are owed nothing, or at most $34-million.

The wide divergence in claims was on display this week in an unprecedented court hearing in Sudbury, Ont., whose purpose is to determine how much the Crown owes for breaking a treaty promise to share wealth produced by the natural resources of a vast area in Northern Ontario.

A lawyer for several Anishinaabe communities collectively made up of about 15,000 people told Ontario Superior Court Justice Patricia Hennessy on Monday that they are owed at least $8-billion, and perhaps as much as $100-billion.

In 1850, Anishinaabe leaders signed two treaties with the Crown that gave over control of resource-rich lands stretching from the north shores of Lake Superior and Lake Huron to Hudson Bay, which today includes the communities of Thunder Bay, Sault Ste. Marie, Sudbury and North Bay.

But the Crown, after paying an initial lump sum of a few thousand dollars, has been making annuity payments capped at just $4 a person since 1875.

Justice Hennessy will be devising a revenue-sharing plan to compensate for the past resource wealth generated on these treaty lands. It will be the first such court-ordered plan in Canada, and it will have enormous practical consequences for thousands of Anishinaabe people in Northern Ontario, who courts have said were left impoverished by the Crown’s neglect of its treaty promise.

Five years ago, Justice Hennessey ruled that the Crown had broken a pledge, set out in two 1850 treaties, to augment the annuity payments as Crown resource revenues permitted. In 2021, the Ontario Court of Appeal largely upheld her ruling.

The judge now has a monumental task: she must determine what revenues to count, what expenses to subtract from those revenues, what interest rate should apply to reflect growth over time and what share of the net revenues should be paid to the First Nations involved.

And on top of all that, she needs to decide which level of government – federal, or provincial – is on the hook for the money owed. On Tuesday, federal lawyer Glynis Evans told Justice Hennessy the vast majority is owed by Ontario. On Wednesday, Ontario’s lawyer, Tamara Barclay, said all of it is owed by the federal government. She added that Supreme Court rulings of the late 19th century had resolved the issue.

But the complications do not end there. Even as four months of hearings got under way this week in a large, makeshift courtroom in Sudbury, the province is still appealing the Ontario Court of Appeal’s earlier ruling on whether the Crown actually did break its treaty promise to share the wealth. That case is pending at the Supreme Court of Canada.

If the Supreme Court overturns that ruling, the entire exercise in Sudbury would be for naught. But given that the First Nations’ lawsuit over the treaty promise began in 1999, and that Anishinaabe elders knowledgeable in oral history and cultural matters are not getting any younger, the Supreme Court rejected Ontario’s request for a stay of the compensation hearings. So did Justice Hennessy.

The First Nations who are parties to the case have shifted. The Red Rock and Whitesand First Nations, who are part of the Robinson-Superior Treaty, have been joined by three other First Nations. Another seven First Nations say they never gave over title to their lands and are trying to win court recognition of that claim (though not as part of the current case). They are represented at the hearings in case they do not ultimately establish that they have title.

Another 21 First Nations are part of the Robinson-Huron Treaty, a territory also addressed by the initial court rulings. This group is now in negotiations with the two levels of government. Their compensation hearing has been adjourned indefinitely.

Harley Schachter, a lawyer representing Red Rock, Whitesand and three other First Nations, likened Ontario’s position that governments owe virtually nothing to that of a fox left in charge of the chickens.

“The fox turns to the judge – got egg all over his face – and in the most reassuring manner and calm tone he can muster says, ‘Look, judge, firstly, about the eggs, there are none, so I don’t know why the chickens are complaining,’” he told Justice Hennessy on Monday, the first day of the hearings.

His clients are claiming an 84-per-cent share of net Crown revenues in five areas, including mining and forestry. The 84 per cent is based on the share of economic risk the First Nations say they took on in the joint venture represented by the treaty.

The higher estimates in the tens of billions of dollars reflect not just what the Crown recouped in various fees, but the higher fees it could have charged if its aim had been to collect on their full value. (Mr. Schachter called this approach “economic rents.”)

On Friday, two-time Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz, an economist, will testify in support of that approach.

“Yes, the final amounts claimed as payable are large,” Mr. Schachter told Justice Hennessy. “They are large because the Crowns did not honour the treaty obligation. They are large but they are not untoward.”

Ms. Barclay, representing Ontario, told Justice Hennessy the province lost $7.9-billion on resources in the territory.

That figure includes the costs of building roads and railways. An alternative approach to determining net revenues would mean $34-million is owed to the Anishinaabe, she said. The First Nations argue that road and railway costs are part of nation-building and should not be deducted from revenues.

Ms. Evans, representing the federal government, said Tuesday the Anishinaabe’s share of net Crown revenues should be roughly 10 per cent, reflecting the ratio of Indigenous to non-Indigenous people in the Robinson-Superior treaty territory. She did not put forward a precise dollar figure, but opposed the “economic rents” approach of the First Nations.

Indigenous Hunting Rights and the NRTA: Case Comment on R. v. Green

|

By Kate Gunn and Nisha Sikka

The question of when and under what circumstances Indigenous people can hunt for food and cultural purposes outside of their province of residence has been a longstanding source of tension and uncertainty, particularly in Canada’s prairie provinces. In its recent decision in R. v. Green, the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal highlighted the lack of clarity in the law on this issue. Below, we consider the implications of the decision for Indigenous hunting rights across Canada. |

Hunting, Treaties and the Natural Resources Transfer Agreements

In the decades leading up to and following Confederation, the Crown entered into a series of treaties with Indigenous Peoples across most of western Canada, including in the region now known as Saskatchewan. The written English versions of most of the treaties provide that the Indigenous treaty parties have the right to continue to hunt on lands throughout the treaty territory until such lands are "taken up" by the Crown for purposes such as non-Indigenous settlement and resource exploitation.

In the 1930s, Canada entered into a series of agreements (the Natural Resources Transfer Agreements, or NRTAs) which transferred the administration and control of Crown lands and resources from the federal to the provincial governments in Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

Paragraph 12 of the Saskatchewan NRTA affirms that Indigenous Peoples in the province possess a right to hunt, trap and fish on all unoccupied Crown lands or on any other lands which they have a right to access. The Alberta and Manitoba NRTAs contain similar provisions.

Today, treaty hunting rights are recognized and protected pursuant to section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982. Courts have further held that the NRTAs are constitutional documents which must be interpreted in light of the Crown’s relationship with and obligations to Indigenous Peoples. For further background on treaties and the NRTAs, see our previous blog post on the Green decision.

The Green Litigation

In 2018 Blair Hill and Albert Green, both from the Six Nations First Nation in Ontario, were charged with unlawful hunting in a provincial park in Saskatchewan.

The trial judge held that Mr. Hill and Mr. Green should be acquitted of the charges because they were exercising a constitutionally protected right to hunt under paragraph 12 of the Saskatchewan NRTA, notwithstanding the fact that both men resided outside the province.

On appeal at the Saskatchewan Court of Queen’s Bench, the Court reversed the trial decision and held that paragraph 12 of the NRTA applies only to Indigenous people who hold rights under the numbered treaties which apply to lands within Saskatchewan. Mr. Hill and Mr. Green appealed to the Saskatchewan Court of Appeal.

What the Court Said

The Saskatchewan Court of Appeal allowed the appeal and set aside the convictions of Mr. Hill and Mr. Green.

The Court held that the question of whether the NRTA provides that all Indigenous people have a right to hunt on unoccupied lands in Saskatchewan, regardless of their province of residence, is an important constitutional issue that will affect Indigenous people residing within and outside the province.

However, the Court held that it was unable to determine the issue based on the evidentiary record before it and ordered that a trial be held with additional historical evidence regarding the negotiation and purpose of the NRTA.

Why It Matters

The Court of Appeal decision affirms that the question of whether the hunting rights set out in the NRTA apply to all Indigenous people, or only those who hold rights under numbered treaties in Saskatchewan, is an issue of significant public importance which must be clarified by the courts.

Rather than resolving the issue, the decision in Green leaves Indigenous people seeking to hunt outside their province of residence in a legal grey area. The ongoing lack of clarity in the law has the potential to foment further uncertainty and conflict regarding Indigenous Peoples’ right to hunt, particularly in provinces which are already grappling with the effects of racism and the Crown’s ongoing failure to honour and uphold its treaty promises.

At the same time, the decision also opens the door for a more robust interpretation of Indigenous hunting rights which takes into account the historical and cultural circumstances which underlie the issues in the litigation. As the Supreme Court of Canada has confirmed, constitutional issues cannot be determined in a vacuum. Based on the direction of the Court of Appeal, the eventual second trial decision in Green could result in a more meaningful understanding of Indigenous Peoples’ rights based on a full evidentiary record.

Looking Ahead

Too often, the rights of Indigenous Peoples have been determined by Canadian courts in the absence of a proper understanding of both the underlying historical facts and the perspectives of the Indigenous Peoples whose rights are at issue.

In some jurisdictions there are signs that this approach is shifting. In recent litigation in Ontario, for example, the Court heard extensive historical evidence as well as evidence from both Anishinaabe and Euro-Canadian witnesses, including experts, Elders and Chiefs, regarding the Crown’s obligations to increase annuity payments to the Indigenous beneficiaries of the Robinson Huron and Robinson Superior Treaties. The Court emphasized that the evidence of the Anishinaabe and Euro-Canadian perspectives were to be treated equally, and that evidence regarding the treaty parties’ understandings and intentions would not be discounted merely because it came from an unconventional source.

The Court of Appeal’s decision in Green suggests a similar shift may be at least partially underway in Saskatchewan. On the one hand, the Court’s emphasis on the need for historical evidence is an important step towards ensuring the interpretation of the NRTA is informed by the historical circumstances in which it was negotiated. At the same time, however, the Court fails to highlight the importance of including evidence regarding Indigenous Peoples’ understandings of the rights guaranteed pursuant to the numbered treaties and affirmed by the NRTA.

As a result, there is still a risk that the issues in Green will be decided without adequate consideration of the Indigenous perspective.

Going forward, it will be for both the parties and the trial judge to ensure that such evidence is included and given weight if the Green litigation is to both clarify the law and advance reconciliation.

First Peoples Law LLP is a law firm dedicated to defending and advancing the rights of Indigenous Peoples. We work exclusively with Indigenous Peoples to defend their inherent and constitutionally protected title, rights and Treaty rights, uphold their Indigenous laws and governance and ensure economic prosperity for their current and future generations.

Chat with us

Kate Gunn is partner at First Peoples Law LLP. Kate completed her Master's of Law at the University of British Columbia. Her most recent academic essay, "Agreeing to Share: Treaty 3, History & the Courts," was published in the UBC Law Review.

In the decades leading up to and following Confederation, the Crown entered into a series of treaties with Indigenous Peoples across most of western Canada, including in the region now known as Saskatchewan. The written English versions of most of the treaties provide that the Indigenous treaty parties have the right to continue to hunt on lands throughout the treaty territory until such lands are "taken up" by the Crown for purposes such as non-Indigenous settlement and resource exploitation.

In the 1930s, Canada entered into a series of agreements (the Natural Resources Transfer Agreements, or NRTAs) which transferred the administration and control of Crown lands and resources from the federal to the provincial governments in Alberta, Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

Paragraph 12 of the Saskatchewan NRTA affirms that Indigenous Peoples in the province possess a right to hunt, trap and fish on all unoccupied Crown lands or on any other lands which they have a right to access. The Alberta and Manitoba NRTAs contain similar provisions.

Today, treaty hunting rights are recognized and protected pursuant to section 35(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982. Courts have further held that the NRTAs are constitutional documents which must be interpreted in light of the Crown’s relationship with and obligations to Indigenous Peoples. For further background on treaties and the NRTAs, see our previous blog post on the Green decision.

The Green Litigation

In 2018 Blair Hill and Albert Green, both from the Six Nations First Nation in Ontario, were charged with unlawful hunting in a provincial park in Saskatchewan.

The trial judge held that Mr. Hill and Mr. Green should be acquitted of the charges because they were exercising a constitutionally protected right to hunt under paragraph 12 of the Saskatchewan NRTA, notwithstanding the fact that both men resided outside the province.